Choked to Death

Bangkoks’ traffic chokes the life from you and brings the city to a dead stop, so I step out of the cab and into a bar. Inside: low light, dirty tables, a lurid drawing of Alice in Wonderland supping tea with the Hatter, and a couple of young Thai men holding their friend, heavily flushed and clinging to a cigarette like a drowning sailor.

At the bar, an eerily still man has his eyes fixed on his half-empty Heineken. He watches me as I put down my backpack and settle at a table. I’m five days cigarette-free, and the nicotinic clouds inside taste better than the streets of smog.

Each time I glance away, the man at the bar moves a little closer, like a boy at a school disco, sidling towards the last girl left uncoupled, until I turn to find his body slumped in the chair next to me, a solitary cigarette silently extended. I take it, allow him to light it with a shaky hand, and breathe in the taste of tobacco with pangs of both relief and disappointment.

He is a peculiar, desiccated man – a broom-straight back, shortly cropped grey hair, thin forearms, prominent Adam’s apple and the first signs of a paunch swelling in the shadows under the table. He says hello, and we settle into the routine patter of expats, talking about the city, visas, places we have lived, the good and bad of the cities of Asia for foreigners. Foreigners, I consider, like us.

His accent is tough to place, and he speaks in half-developed answers, with long pauses between every few words. I comment on the (excellent) Atlanta hotel where I am staying (a large sign outside the grand old place says NO SEX TOURISTS ALLOWED), which leads to an inelegant segue where he informed me that he spent last night with some girl or other, which I took as a chance to go to the toilet.

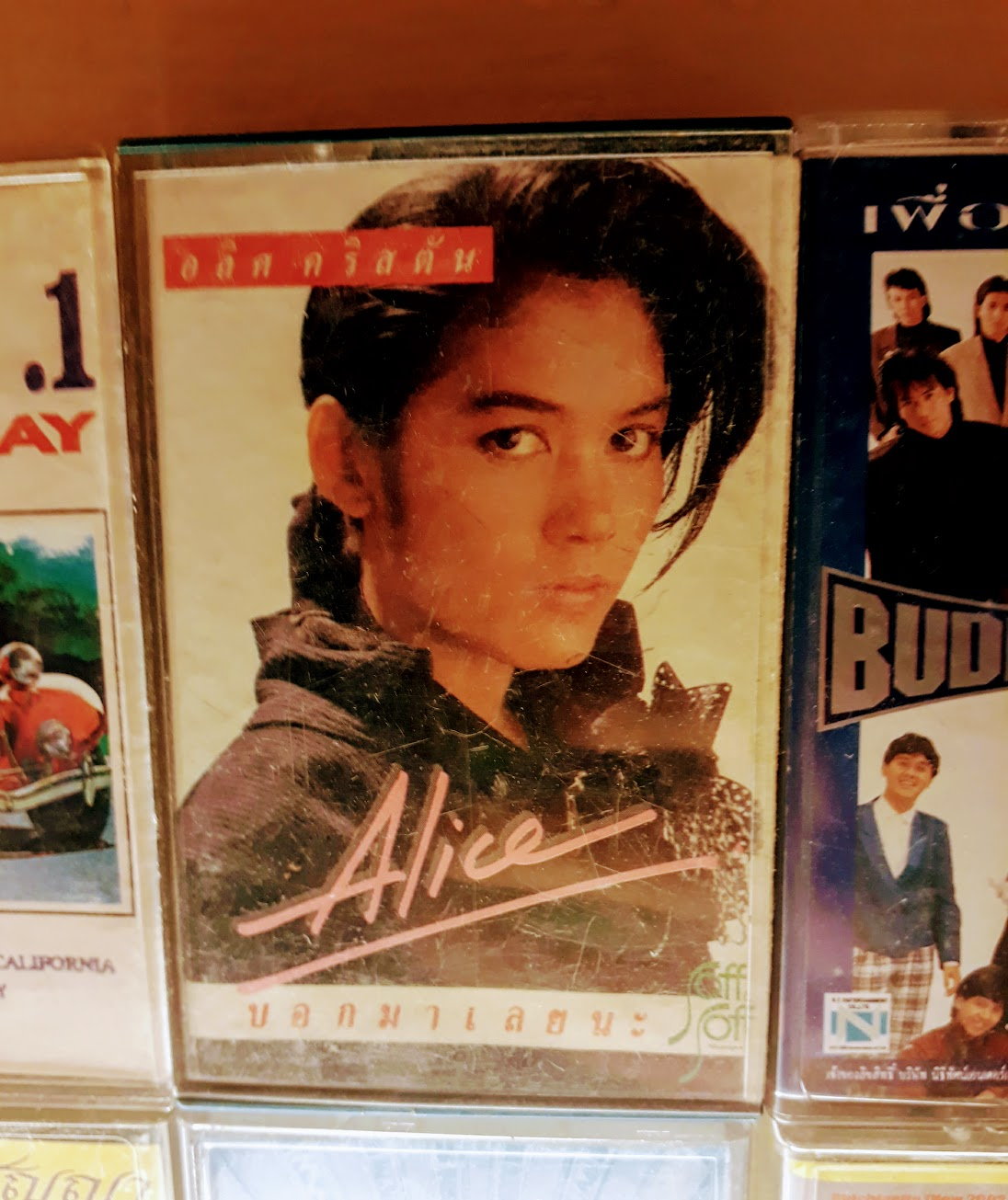

As I dry my hands, I stare at a pile of cassette tapes inexplicably stacked against the wall. One catches my eye, a photo of a girl with a denim jacket, quiff, and a flower tucked into her coat.

When I return, the man is staring into space, still as an ancient tree, and two more beers have appeared before him. Outside, the horns are still sounding, I have at least half an hour to kill

Sooner or later, I will get his life story, and I am almost relieved when it came sooner. He was here to consider business opportunities after inheriting a large amount of money from his father.

“Ja, it vas most sad what is happening to him.”

“What happened?”

“He choked”

“Oh. I’m sorry,” I say.

I wondered if I should share my choking anecdotes – a piece of rogue chicken in a Marks and Sparks premium Korma had put me in hospital, a result of me attempting to inhale the whole meal in under a minute in a fit of teenage haste.

As I began to asphyxiate, I got angrier and angrier, the edges of my vision moving together, the world disappearing behind a curtain. On my knees, one hand on my desk chair, I repeatedly punched myself in the throat, until, likely with seconds to spare, I hit myself hard enough to dislodge the food and draw in a shuddering breath. It took three days in a hospital bed and surgery under anaesthetic to clear my throat, and I have to carefully chew my food these days. Like a boxer who gets his bell rung, since that one incident, I’m vulnerable to choking, and I feel a swell of sympathy..

“Ja,” he says solemnly. “He was upstairs in the townhouse back in Bardenwurtenschlieefenhausgebraunurstrand, and he was just sitting there, eating an orange. It was my mother who found him. His wife.”

“An orange killed your dad?”

He nods sadly.

“Not even ze hard part. The soft part of the orange, how are you calling it?”

“The flesh?”

“Ja, zis. Ze flesh of ze orange.”

I stared, a little bleary-eyed, at my beer. If the man hadn’t been so utterly humourless, I might have thought he was fucking with me. But he was paying for the drinks, and there was no audience, so it would have been a strange trick indeed. Besides,

“I’m sorry to hear about your father choking to death on an orange.”

He nodded solemnly. “He was 96. He left me all his money. You have lived in Vietnam. How would you move some money into the country?”

In my experience, getting money into Asian countries is no problem. – it’s getting it out that’s hard.

“How much?”

“Ten million dollars,” he said.

The man stares at me, with citrus juice stinging his wounds and ten million dollars weighing heavy on his mind. His watery Teutonic eyes swim under the bar lights. No brothers, no sisters, some new girl in his bed every night. I felt a sting of pity for this rudderless man, buying drinks for strangers and asking their advice about moving ten million dollars, pity mixed with revulsion, as though this man was a spectre of some dark and hidden future. I put my money on the table and moved towards the street, even though the crush of cars was as thick as ever, and the smoke continued to stick in people’s lungs.

I wondered what Alice was doing right now. She would be old. At least 40, I thought.

“I don’t know.” I said, “I’m sorry. Good luck.”